SEATTLE – A rosary that belonged to Princess Angeline, Chief Seattle’s daughter Kikisoblu, was gifted to the Duwamish Tribe by the Archdiocese of Seattle Nov. 9.

“Because she is the daughter of our chief … to have that little rosary coming back to the tribe, that is so moving. To me, it’s really spiritual,” said Cecile Hansen, Chief Seattle’s great-great-grandniece who is a lifelong Catholic and the longtime chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribal Council.

“Being a Catholic myself, and I say the rosary all the time, it’s really moving to find out that we knew that (Princess Angeline) became a Catholic and so did her dad, toward the end of his life,” said Hansen, who attends St. Thomas Parish in Tukwila and St. Francis of Assisi Parish in Burien.

Princess Angeline’s rosary, part of the archdiocese’s archives collection, was on loan for more than a decade to MOHAI, the Museum of History and Industry, which had it on display. Last May, Duwamish members asked the archdiocese to give them the rosary so it could be displayed at their longhouse museum with other items belonging to Chief Seattle and Princess Angeline.

With the approval of Archbishop Paul D. Etienne, the archdiocese agreed to gift the rosary to the Duwamish, with the desire that it be on display at the longhouse, according to Seth Dalby, the archdiocese’s director of archives and records management.

When everyone’s schedules finally aligned, about a dozen people gathered at the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center Nov. 9 to participate in the transfer.

With a large portrait of Princess Angeline as a backdrop, Deacon Carl Chilo, director of Multicultural Ministries for the archdiocese, blessed the rosary and sprinkled it with holy water. Then Josh Zimmerman, archivist/records manager for the archdiocese, presented the rosary to Hansen. The rosary was passed around so others could see it up close; some people snapped photos.

“I think this is incredibly symbolic and incredibly special,” said Aurora Martin, advisory general counsel for the Duwamish, who was among those requesting the rosary’s transfer. Martin, who attends Seattle’s St. John the Evangelist Parish as well as St. James Cathedral, called the rosary “an incredibly special artifact” and its transfer to the tribe “really a kind of spiritual reawakening.”

Chief Seattle’s Catholic roots

Chief Si’ahl (called Seattle by the region’s settlers) was born around 1786; his father was Suquamish and his mother was Duwamish, according to research done by Corinna Laughlin, pastoral assistant for liturgy at St. James Cathedral who has written many articles about the history of the archdiocese.

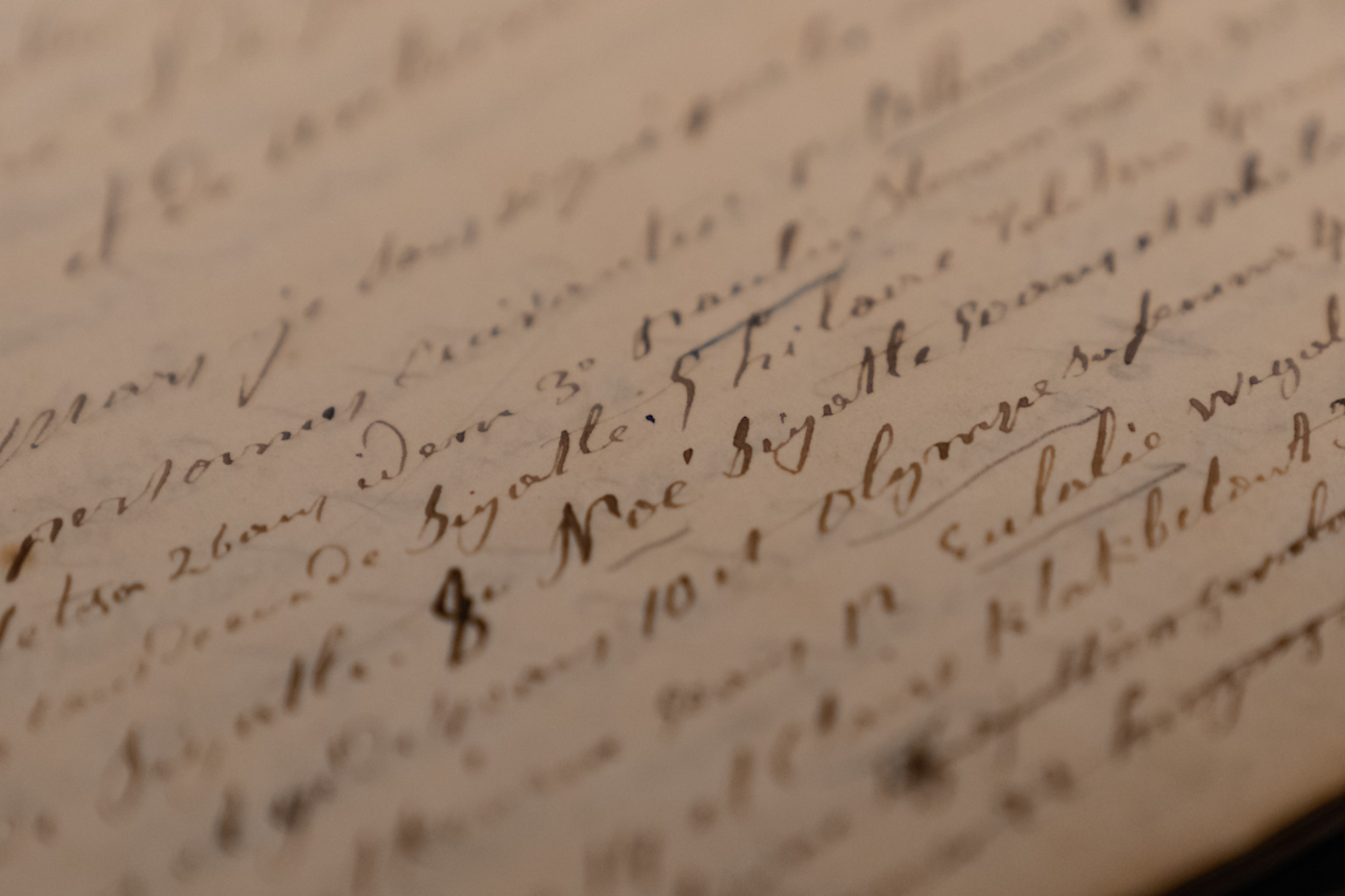

It was known that Chief Seattle was confirmed in 1864 and married in the Catholic Church in 1865; when he died in 1866, he was buried at St. Peter’s cemetery at Suquamish, Laughlin said in a presentation at the cathedral in August. But his baptismal record wasn’t found until 2018, when Joan Byrne, an archives volunteer, was translating sacramental registers written in French by missionary priests. The record shows he was baptized Noé (Noah) Siyatle on March 17, 1857, when he was about 71 years old.

Chief Seattle had encountered Christian missionaries his whole life, Laughlin said, but choosing to be baptized Catholic late in life was “a very intentional decision on his part.” It would have been a difficult choice, she said, because “Catholics weren’t necessarily welcome” in an area where all the leaders were Protestant. “Chief Seattle was not just Catholic, but a serious and quite intentional Catholic,” Laughlin added.

From Kikisoblu to Princess Angeline

Kikisoblu, Chief Seattle’s daughter by his first wife, also was Catholic; she had two daughters and named them Mary and Elizabeth. Kikisoblu became friends with some of the Seattle pioneers, including Catherine Maynard, who gave her the name Angeline because she thought it was prettier and easier to pronounce, Laughlin said. And because she was Chief Seattle’s daughter, she became known as Princess Angeline.

“Although the settlers named the city Seattle, shortly afterward Native people weren’t allowed to be inside the city limits,” Laughlin said. Angeline didn’t leave and “for whatever reason she was allowed to remain in the city, but her people were not, so she lived quite isolated from the rest of her tribe,” Laughlin added.

Angeline lived in a shack on the downtown waterfront and earned a living doing laundry and making baskets. She got a lot of attention as Chief Seattle’s daughter; many photographs were taken of her and used on all kinds of souvenir items, Laughlin said.

“She got a dollar typically when somebody took a photo of her, but she didn’t get anything for the millions of reproductions of her pictures,” Laughlin added.

Always with her rosary and crucifix

“Princess Angeline was known for always having a cigarette,” Laughlin said, “but the other thing that’s not so well known is that she was always with her rosary and her crucifix.”

Angeline would say, “I am a Catholic and I have a crucifix and a rosary.” Showing her crucifix to people, she would say, “this is my friend,” Laughlin said.

And, as the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary recorded in their house chronicles, “it was no infrequent sight to see this poor old Indian woman seated on the sidewalk devoutly reciting her beads.”

Angeline also was a regular worshipper at Our Lady of Good Help Church in Pioneer Square, which was later moved and rebuilt a few blocks away, according to Laughlin. One of the pioneer church’s treasures, the statue of Our Lady of Seattle, can be found today in the chapel at St. James Cathedral, where Laughlin gave her presentation.

“This statue … is our special connection with Princess Angeline,” Laughlin said, “because she was a parishioner at that church and would have prayed before this image many times.”

And the rosary that belonged to Princess Angeline “is a really significant object” because of who it belonged to and because it’s a reminder “of the intersection of the Catholic faith with the beginnings of Seattle,” Laughlin said.